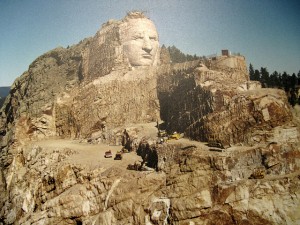

You might be interested in a progress report on what many believe is the largest and grandest stone carving ever attempted — if you can call blasting out of solid rock a mountain-sized figure of a man on horseback a “carving.”

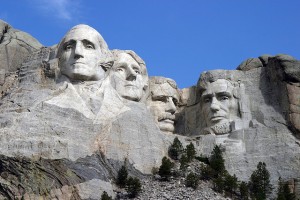

It’s appearing, slowly, methodically, but unmistakably, in the Black Hills of South Dakota, just 13 kilometers (8 miles) from the park where the famous stone busts of presidents George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, and Theodore Roosevelt loom atop Mount Rushmore.

In the 1940s, when sculptor Gutzon Borglum’s work was finished on Rushmore’s granite façade, a Lakota Sioux chief, Henry Standing Bear, wrote Borglum’s assistant, Korczak Ziółkowski, a Polish immigrant from Boston whose marble bust of Polish pianist and statesman Ignacy Paderewski had won first prize by popular vote at the New York World’s Fair in 1939.

You have come to our sacred mountains with dynamite and picks and gas-powered jackhammers to build a monument to great white men, Standing Bear told Korczak (his family and everyone else I’ve met in South Dakota calls him by his first name, so I will as well). Why not create a monument to honor the greatest of red men as well?

Korczak agreed, and in 1948 on Thunderhead Mountain, he began work on a pink-granite monument to Chief Crazy Horse astride a charging horse. “Every man has his mountain,” Korczak said. “I’m carving mine.” He had $174 to his name when he began.

Ironically, perhaps eerily, Korczak was born on September 6, 1908, 31 years to the day after Crazy Horse was slain. Many Indians consider that an omen.

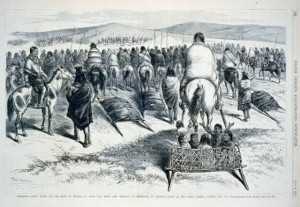

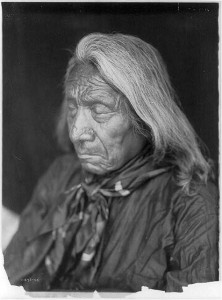

These Indians were photographed at the Pine Ridge Agency, or reservation, in South Dakota. (Library of Congress)

Korczak called the treatment of American Indians in the years after they were driven off their lands “the blackest mark on the escutcheon of our nation’s history. By carving Crazy Horse, if I can give back to the Indian some of his pride and create the means to keep alive his culture and heritage, my life will have been worthwhile.”

Korczak’s mountain rose in a scraggly patch of pine forest reached by no highway, no electricity, and no running water. So the project on which he spent the last 30 years of his life is a tribute to amazing logistics as well as astounding art. Korczak worked alone until his children were old enough to pitch in. For years he climbed 741 wooden steps that he had built up to the ridge atop which Crazy Horse’s face would emerge. One day, he made that up-and-down trek nine times when his balky old compressor below kept sputtering to a stop.

His subject, Crazy Horse — Sioux name Tashunka Witko — was a fascinating and controversial choice.

He was the fiercest of Sioux warriors in the years when these nomadic people fought desperately to retain their way of life against whites who broke treaty after treaty and pushed steadily into their sacred lands and hunting grounds.

Carol's distant photo of the sculpture and mountain gives you an idea of its grand scale. (Carol M. Highsmith)

An old chief and spiritual leader named Sitting Bull brought the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes together for a showdown with white soldiers on the Little Bighorn River in Montana Territory in 1876.

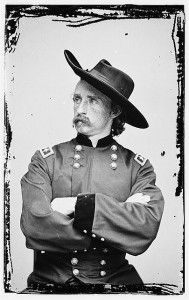

But it was Crazy Horse, a warrior in his 20s, whose ferocious visage — red hawk-feather headdress, long hair flying, face painted with a lightning bolt — led braves into battle that turned into the annihilation — whites called it a “massacre” — of U.S. Army general George Custer and all 210 of his men.

Golden-haired General Custer had been a hero in the American Civil War, and most Sioux soon realized that although they won the Battle of the Little Bighorn, they would face unrelenting revenge and inevitably lose the struggle to save their lands. More soldiers and more guns would follow Custer.

So these wandering people laid down their bows and lances and guns, and grudgingly moved into confinement on reservations.

The great Sitting Bull was reduced to accepting payment for humiliating appearances in “savage” Indian make-up in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows.

But not Crazy Horse.

He fought on, leading other bloody raids on whites’ wagon trains and encampments. So you can see why many white Americans did not regard Crazy Horse as a fitting figure to tower for all time in South Dakota’s piney foothills of the Rocky Mountains. They likened it to erecting a statue to Mexico’s General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, whose force of 5,000 men slaughtered about 185 Americans defending the Alamo mission in Texas in 1836; or Naval Marshal General Isoruko Yamamoto, who commanded Japan’s sneak attack on Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor in 1941, sinking or badly damaging 16 U.S. warships and killing more than 2,400 servicemen and women and civilians.

Pursued by troops and driven to the point of starvation, Crazy Horse and his band eventually surrendered. Crazy Horse, defiant as always in captivity, was bayoneted and killed by a nervous young soldier at Fort Robinson in Nebraska.

Not once did the rebellious war chief sign a treaty. Nor, so far as anyone knows, was he ever photographed. Unlike Sitting Bull, he certainly never posed placidly for a white man’s painting.

So what did he look like?

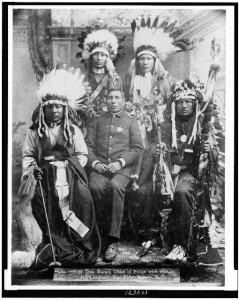

In 1948, Korczak Ziółkowski was fortunate to meet five elderly Lakota Sioux survivors of the 1876 Little Bighorn battle. They described Crazy Horse as a small man with loose, flowing hair, a stone worn behind one ear, and a facial scar left by a U.S. Army rifleman’s bullet. Since the memorial on Thunderhead Mountain was intended as a monument to all Indian people, Korczak was pleased that other details could be left to his imagination.

His task was supported by donations alone and no federal or state funds. To this day, workers collect pieces blasted from the mountain and place them in a “rock box,” from which visitors can pick them up, leave donations, and take them home. The rock box alone generates about $100,000 a year.

Korczak worked until he died in 1982. During all his years of work on Thunderhead Mountain, he refused to accept a salary.

Ruth Ziolkowski stands before a photo of Korczak and Chief Henry Standing Bear. (Carol M. Highsmith)

His wife, Ruth — who met Korczak as a teenager in West Hartford, Connecticut, where Korczak was creating a sculpture of Noah Webster, the creator of America’s first dictionary — has continued his work and dream, along with 7 of their 10 children. Korczak had left them a letter that read, “You don’t have to do this. But if you do, don’t ever let it go.”

The American people have Mount Rushmore, the Statue of Liberty, and other great monuments,” Ruth Ziółkowski told me many years ago. “The Indian people really need a memorial.”

And in 2009 we talked again. “Korczak used to laugh and call himself “the world’s greatest chiseler,” she told me, delighting in the double meaning of the word. More formally, he referred to himself as “a storyteller in stone.”

But his most famous, and apt, quote is the following:

“Go slowly so you get it right.”

__

A quick interruption to tell you that at the end of the podcast of this blog, I have added my full audio interview of Ruth Ziółkowski, in the event you’d like to hear more about her husband’s lifetime project.

—

You want scale? Carol and I are standing on an outcropping next to the carving of just Crazy Horse's head.

The carved, granite head of Crazy Horse alone stands 27 meters (87 feet) tall. In the past decade, the first outlines of the warrior’s horse have taken shape below him. When completed, the total work will rise a staggering 172 meters (563 feet). That’s three meters taller than the Washington Monument and 25 meters higher than the Pyramid of Giza.

“My father did the hard part,” Korczak Ziółkowski’s son Casimir, who now directs the carving, told me. “He got everyone to believe. He got it far enough along so that all we have to do is show up and go to work.”

More gets done in the cold, snowy South Dakota winter, surprisingly, than in its balmy summer, due in part to the area’s violent thunderstorms. The work has roughly followed the same techniques as Borglum used at Rushmore, beginning with a three-dimensional measuring system that enables the sculptor to create a manageable scale model.

This angle, from farther away, shows work in progress on Thunderhead Mountain. (clkohan, Flickr Creative Commons)

With it as a guide, workers began a systematic series of dynamite blasts on the granite mountainside. Very careful blasts. After all, it wouldn’t do to have a war chief’s nose break off during the excavation.

As 8 million tons of rock (so far) have been loosened and the rubble bulldozed off Thunderhead Mountain, the Crazy Horse colossus in the round — this is no bas-relief — has been honed using supersonic torches. One of the trickiest maneuvers was blasting a hole, 10 stories high, clear through the mountain to create the space between Crazy Horse’s left arm, which points out across his beloved Black Hills, and his stone horse’s mane below.

The gesture represents what the warrior is said to have told his captors: “My lands are where my dead lie buried.”

“This is a living memorial to a man and an entire people,” one of the mountaineering workers at the site told me. “It’s embossed in stone, there for a lifetime. Who wouldn’t want that?”

This angle, from farther away, shows work in progress on Thunderhead Mountain. (clkohan, Flickr Creative Commons)

Who would not want it? As I mentioned, those who find Crazy Horse’s deadly attacks barbaric, for one. And some Indians, too. Lymon Red Cloud, great grandson of another Sioux warrior, Chief Red Cloud, told me that he and other Sioux resent white men building another monument — even one to an Indian — on sacred land.

This is wrong. Very wrong. As an honor, we give eagle feathers. And Crazy Horse has received eagle feathers from our people for honor and for recognition. But the white people cannot give him eagle feathers.

Interviewed in 2001, Indian activist Russell Means, an Oglala Sioux, objected even more stridently. “Imagine going to the Holy Land in Israel, whether you’re a Christian or a Jew or a Muslim, and starting to carve up the mountain of Zion. It’s an insult to our entire being.”

In 2009, New York Times columnist Lawrence Downes wrote that Sioux artist Kelly Looking Horse told him “there were probably better ways to help Indians than a big statue.”

Of course, there’s no putting a dollar value on its potential beneficial effect on the pride of a demoralized people.

Ruth Ziółkowski reminds critics that it was at a Sioux chief’s request that her husband began work on the Crazy Horse sculpture. “I think the concept was good and the idea was good 50 years ago,” she told me in 1997. “And I’m sorry that it may not be now because times have changed. But we’ve started and certainly wouldn’t stop.”

This ill-lilt painting of Korczak and Standing Bear hangs in the visitor center. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Twelve years later, she reminded me that American history has largely been written by whites. “You can’t blame Crazy Horse for what he did,” she said. “Imagine if someone was trying to take this country from us. Wouldn’t you be proud of someone who stood up and fought the invader?”

Plans for the valley in Crazy Horse’s shadow call for a hogan-style Indian Museum of North America, and a new university campus to serve American and Canadian Indians from across the continent.

And everyone I’ve talked with agrees that this site and the Mount Rushmore tribute to U.S. presidents should be the last mountains disturbed in the Black Hills.

There’s one last, ironic twist to the story.

Remember the fair-haired general whom Crazy Horse defeated in battle? Guess what’s the name of the closest town to the warrior’s great stone monument?

It’s Custer, South Dakota.

You can see the monument far in the distance beyond Korczak's model of it. (Mike Tigas, Flickr Creative Commons)